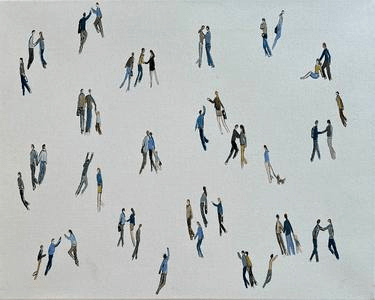

Do you remember, those first weeks and months of the pandemic, the examples of nature – the animals really – reclaiming their spaces? The half-joking comment always attached to it, “nature is healing, we are the virus.”

The juvenile mountain lion wandering a sidewalk in an empty San Francisco neighborhood. Bats roosting for the first time in over 20 years at Timpanogos Cave National Monument in Utah. Sea turtles returning to the Greek Isles. Bison and bears remembering that their old migratory corridors were though now-abandoned parking lots and picnic areas. With cleaner air and more insects to eat, swifts laid more eggs in their clutches. After traffic across the north Atlantic quieted to nothing, right whales could hear each other again, singing across ocean basins to their cousins, not needing to pause and let a ship pass by. Javelinas took up on street corners in Phoenix. Mountain goats wandered down from their high altitudes into Welsh cities. Water quality improved around some coral reefs, with snorkeler fins gone and no sediment getting kicked up. So did the abundance and diversity of fish. Sparrows could sing more quietly, expend less energy, live longer lives.

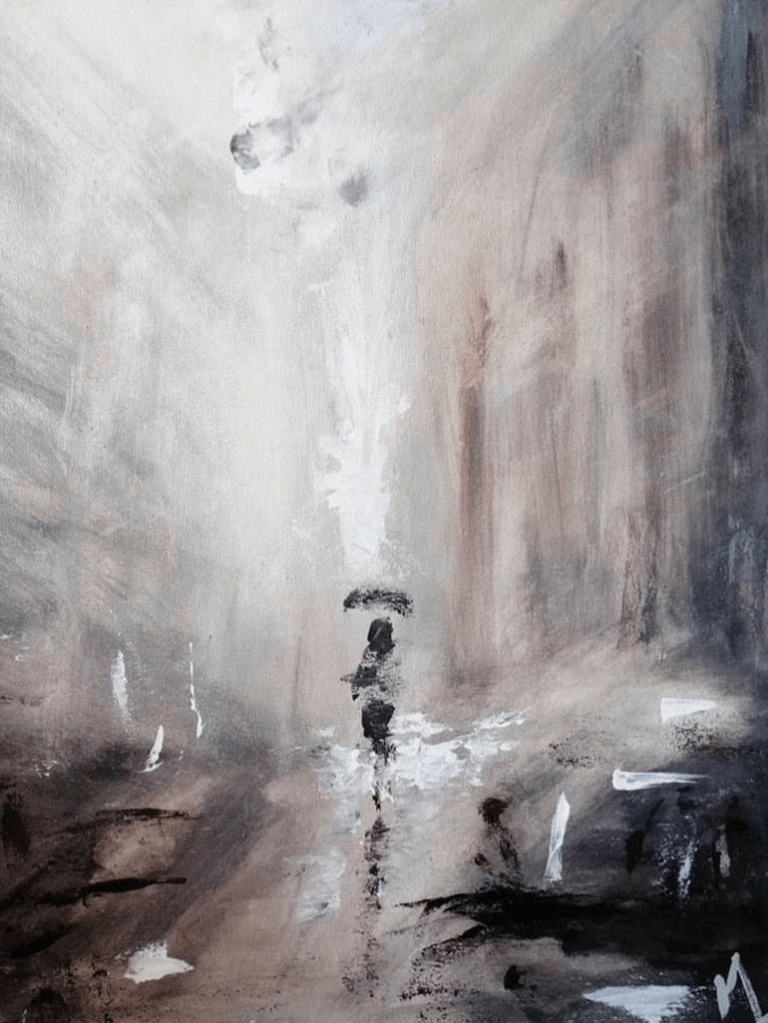

Yet, it wasn’t all this positive. We humans having created a real mess of moving species from one place to the next, feeding them, overharvesting them because our food systems are brittle, disrupting the natural order of things in our attempt to control the natural order of things, to have power over, to forget that ultimately, we, too, are animals. In a kingdom that wasn’t created for us, depending on what you believe, but that we keep trying to create for us. We keep trying to burn it, shape it, mold it, slash it, cut it, raze it, bomb it, dig it. We now have fire storms, thunder snow, extreme heat, and atmospheric rivers alongside dry riverbeds, expanding deserts, snowless mountain caps, and thinning ice.

My dream for all those winged, feathered, furred, finned, scaled, and legged animals is to go. To outrun us. To outlast us. To outsmart us. Like the camouflage of the cuttlefish, projecting their millions of neurons onto expandable pixels in their skin, fading from visual definition and discernment into the depths of the rocky sea bottom. Or the leafy sea dragon wrapping itself around the vivid green seagrass, gently, casually, swaying as one being in the ocean current. The snow lotus up in the sky, nestled among the clouds, thin air and ice of the Himalayas, muting its brightness to live another day. The eyelash leaf-tailed gecko merging into the tree trunks of Madagascar. The sand crab. The ghost mantis. The stone flounder. The snowy owl. The mossy frog. The leaf katydid.

I want you to take inspiration from them all.

To adapt.

To survive.

To take flight, in unison.

No time to look back.

I just want to say go. Go fast. Go while you still can.